_Reactive programming is a programming paradigm/pattern where the focus is on developing asynchronous and non-blocking applications in an event-driven form Ex: - Project Reactor

Drawbacks in the traditional way

-

Once a thread is assigned to a request that thread won’t be available until that request finishes its process.

-

If all the threads are occupied, the next requests that come into the server will have to wait until at least one thread frees up.

-

When all the threads are busy, performance will be degraded because memory is being used by all the threads.

-

Asynchronous and non-blocking

Asynchronous execution is a way of executing code without the top-down flow of the code. In a synchronous way, if there is a blocking call, like calling a database or calling a 3rd party API, the execution flow will be blocked. But in a non-blocking and asynchronous way, the execution flow will not be blocked. Rather than that, futures and callbacks will be used in asynchronous code execution. -

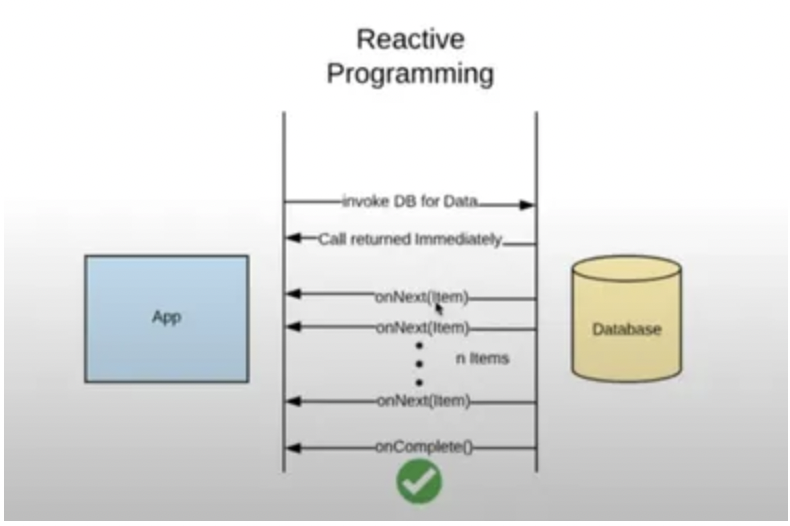

Event/Message Driven stream data flow

In reactive programming, data will flow like a stream and because it is reactive, there will be an event and a response message to that event. In Java, it is similar to java streams which was introduced in Java 1.8. In the traditional way, when we get data from a data source (Eg: database, API), all the data will be fetched at once. In an event-driven stream, the data will be fetched one by one and it will be fetched as an event to the consumer. -

Functional style code Similar to java 1.8 Lamda expression. In reactive programming, we mostly use this lambda expression style. Back Pressure In reactive streams when a reactive application (Consumer) is consuming data from the Producer, the producer will publish data to the application continuously as a stream. Sometimes the application cannot process the data at the speed of the producer. In this case, the consumer can notify the producer to slow down the data publishing.

Reactive stream specifications:

Java reactive programming provides 4 interfaces, which needs to be extended to while creative reactive stream.

- Publisher: Single method interface, to register subscriber to producer

public interface Publisher<T>{ public void subscribe(Subscriber<? extends T> s) ; }

1. Subscriber

This is an interface that has four methods

**_onSubscribe_** method will be called by the publisher when subscribing to the Subscribe object.

**_onNext_** method will be called when the next data will be published to the subscriber

**_onError_** method will be called when exceptions arise while publishing data to the subscriber

**_onComplete_** method will be called after the successful completion of data publishing to the subscriber

```Java

public interface Subscriber<T>{

public void onSubscribe(Subscription s);

public void onNext(T t);

public void onError(Throwable t);

public void onComplete();

}

- Subscription

public interface Subscription{

public void request(long n); // calls when subscriber wants to request data from publisher

public void cancel(); // method called when subscriber wants to cancel the subscription

}- Processor

public interface Processor<R,T> extends Subscriber<R>, Publisher<T>Challanges and solution of reactive programming

Error handling challenges:

- Non-Blocking Nature: Reactive programming relies on non-blocking operations, which can lead to errors occurring at different times and potentially being handled on different threads. This makes traditional error handling mechanisms, like try-catch blocks, less effective.

- Asynchronous Stack Traces: Asynchronous operations can complicate stack traces, making it harder to track down the source of errors and their context.

- Multiple Stages: Reactive chains often consist of multiple stages with various transformations and operators. Errors could occur at any stage, making it important to handle them at the appropriate level.

Strategies to handler error in reactive programming

onErrorResumeandonErrorReturn: These operators allow you to provide fallback values or alternative streams in case of an error.doOnError: This operator lets you execute specific actions when an error occurs, such as logging the error or cleaning up resources. It doesn’t interfere with the error propagation itself.retryandretryWhen: These operators enable you to automatically retry an operation a specified number of times or based on a certain condition.

Backpressure

Reactive programming provides a more interesting feature, backpressure.

Imagine a scenario where a fast data producer is feeding a slow data consumer. Without backpressure, the consumer could become overwhelmed, leading to memory exhaustion, latency spikes, or even application crashes.

Backpressure Handling Strategies

- BUFFER: The most straightforward strategy. The publisher buffers emitted data until the subscriber can consume it. While this can prevent data loss, it might lead to increased memory usage.

- DROP: When the subscriber signals that it can’t keep up, the publisher simply drops the excess data. This can lead to data loss but helps prevent memory overflows.

- LATEST: This strategy drops the previously buffered data and only keeps the most recent data. It’s useful when older data becomes less relevant.

- ERROR: The publisher throws an error when the subscriber can’t keep up. This strategy ensures that backpressure issues are surfaced explicitly but can be disruptive.

Flux<Integer> fastProducer = Flux.range(1, 1000);

Flux<Integer> bufferedConsumer = fastProducer.onBackpressureBuffer(10);

bufferedConsumer.subscribe(

value -> {

// Simulate slow processing

Thread.sleep(100);

System.out.println(value);

}

);Reactive async Web client

// create client

Mono<ClientResponse> responseMono = webClient.get()

.uri("/endpoint")

.retrieve()

.toBodilessEntity();

// Call get method via client

Mono<ApiResponse> responseMono = webClient.get()

.uri("/endpoint")

.retrieve()

.bodyToMono(ApiResponse.class);

// consumer

responseMono.subscribe(

response -> System.out.println("Response: " + response),

error -> System.err.println("Error: " + error.getMessage())

);Challenges of Reactive programming

Increased Complexity: Reactive systems require a different mindset. Composing asynchronous streams, handling backpressure, and coordinating multiple reactive sources can be harder to design and maintain compared to traditional imperative code. Steep Learning Curve: Debugging and Error Handling Tracing errors in asynchronous, non-blocking flows is more difficult. Stack traces can be fragmented or non-intuitive because the call stack doesn’t necessarily follow the logical flow of operations. Tooling and Testing: Writing effective tests for asynchronous flows may require specialized testing frameworks (like WebTestClient or StepVerifier). Interoperability: Integrating reactive code with legacy or blocking code can be challenging. Careful attention is needed when mixing paradigms to avoid performance bottlenecks.

It can be memory intensive

Reactive pipelines are built by chaining many operators (e.g., map, flatMap, filter). Each operator can create intermediate objects (e.g., context wrappers, lambdas) that remain in memory until the entire chain completes. This can add up, especially in complex pipelines. Maintaining context across asynchronous boundaries requires additional memory Buffering and Backpressure:

To manage asynchronous flows and handle bursts of data, reactive streams often use buffers. When the downstream consumer is slower than the upstream producer, the framework buffers items until they can be processed. If backpressure isn’t applied correctly or if the system is overwhelmed, these buffers can grow and increase memory usage. Concurrency and Task Scheduling:

Reactive systems run many small tasks concurrently using event loops or thread pools. Although these tasks are lightweight, having a large number of them in flight at once may increase memory overhead compared to a more synchronous, linear approach.

Performance matrix

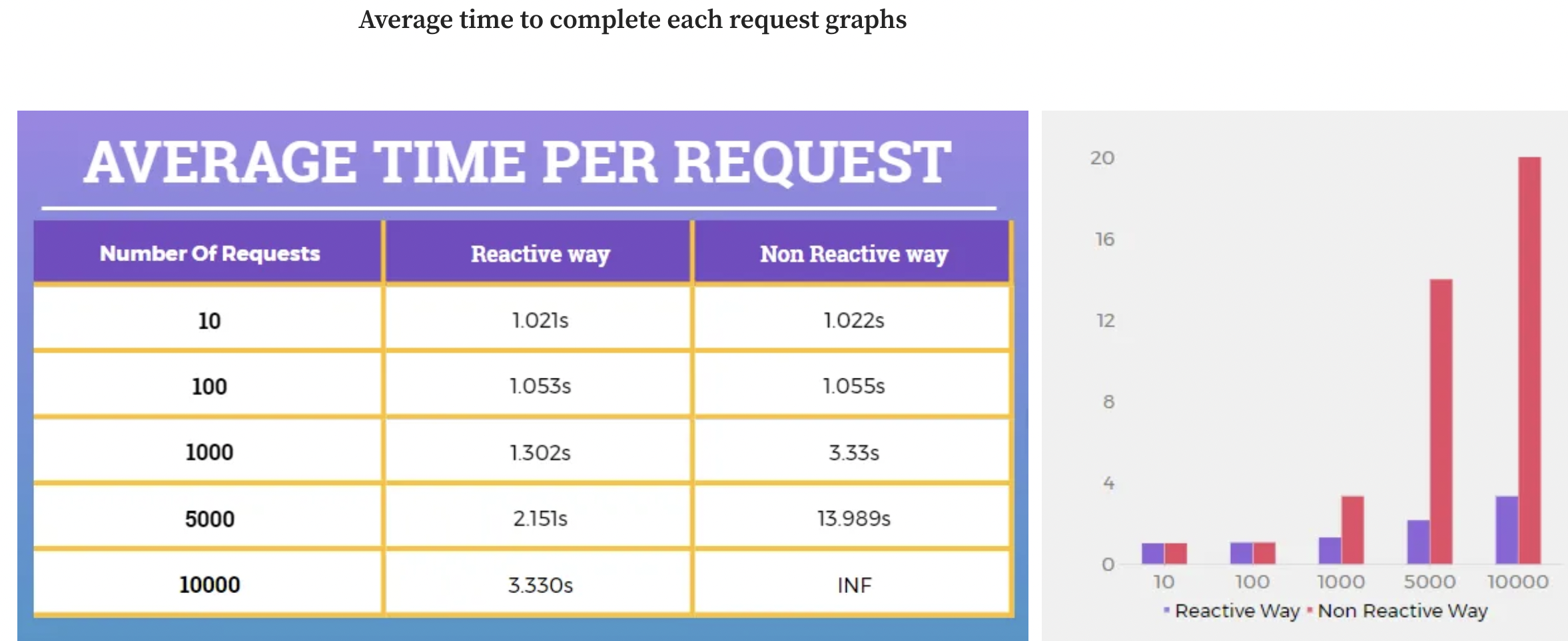

1st expirement

Called the endpoint with 10, 100, 1000, 5000, 10000 number requests and recorded the average time to complete each request and also the time to complete all requests

(10000 requests for the Non Reactive way could not be handled in my machine due to limited resources. Hence, I assume that it is infinity (INF)).

(10000 requests for the Non Reactive way could not be handled in my machine due to limited resources. Hence, I assume that it is infinity (INF)).

For both Reactive and Non Reactive, it takes pretty much the same time to complete its process when using a lower number of concurrent request. However, we see a large difference when it comes to a higher number of concurrent requests. With this, we can conclude that the reactive approach is useful for applications that will be used by a large number of users at the same time.

_The reactive approach is useful for applications that will be used by a large number of users at the same time. It saves memory by completing all the processes in less time, so upcoming requests can be utilised without delay and failures.

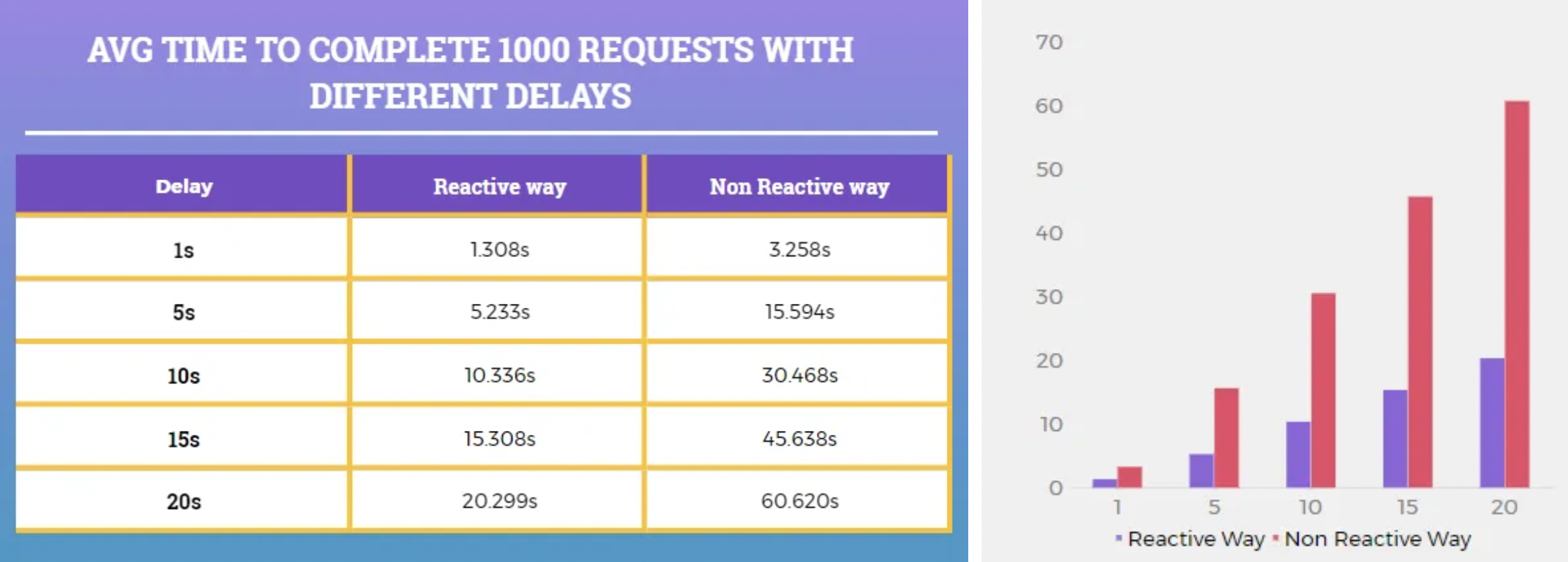

2nd Expirement

Called 1000 concurrent request by adding different delays. The delays are 1sec, 5sec, 10sec, 15sec, 20sec.

we can observe the is a large difference in the time between the reactive way and the nonreactive way to complete heavy time-consuming tasks. In the reactive way, it takes much less time to complete the bulk of time-consuming tasks. It saves memory by completing all the processes in less time, so upcoming requests can be utilised without delay and failures.