Core Requirements

- Users should be able to submit a long URL and receive a shortened version.

- Optionally, users should be able to specify a custom alias for their shortened URL.

- Optionally, users should be able to specify an expiration date for their shortened URL.

- Users should be able to access the original URL by using the shortened URL.

Below the line (out of scope):

- User authentication and account management.

- Analytics on link clicks (e.g., click counts, geographic data).

NFR

- We need to ensure that the short codes are unique.

- We want the short codes to be as short as possible (it is a url shortener afterall).

- We want to ensure codes are efficiently generated.

- Low latency redirection

- Scalable to 1B urls

- System should be available

APIS

`// Shorten a URL POST

/urls

request- >

{

"long_url": "https://www.example.com/some/very/long/url",

"custom_alias": "optional_custom_alias",

"expiration_date": "optional_expiration_date"

}

Response -> { "short_url": "http://short.ly/abc123" }`

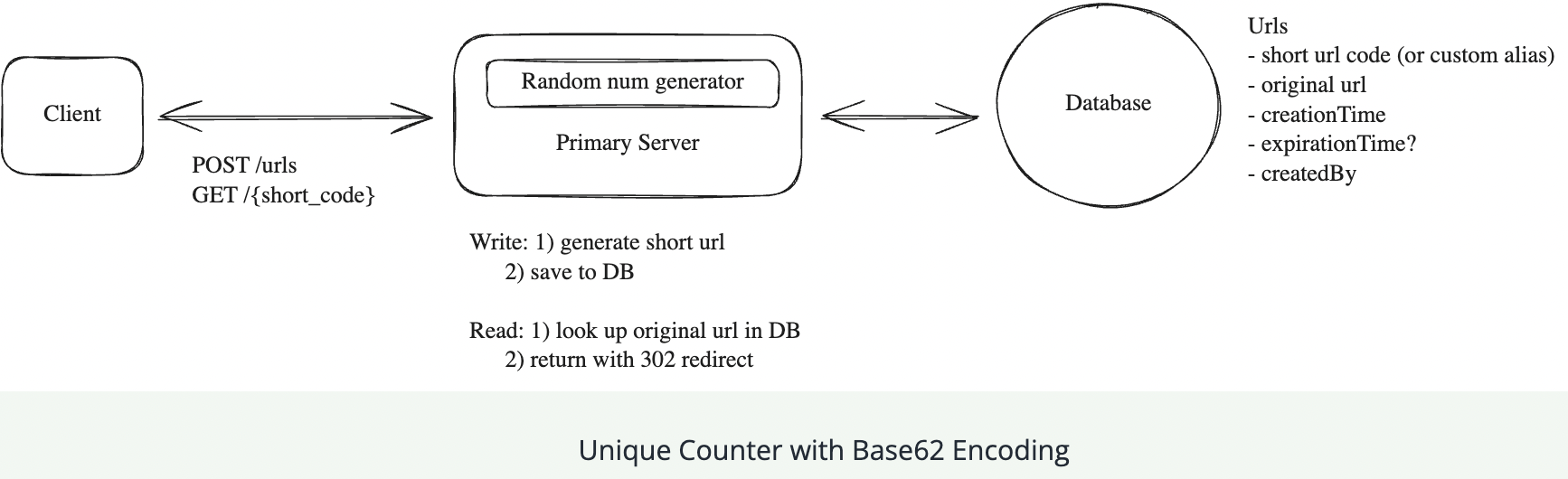

For redirection, we'll need a GET endpoint that takes in the short code and redirects the user to the original long URL. GET is the right verb here because we are reading the existing long url from our database based on the short code.

`// Redirect to Original URL GET

/{short_code}

-> HTTP 302 Redirect to the original long URL`There are two main types of HTTP redirects that we could use for this purpose:

- 301 (Permanent Redirect): This indicates that the resource has been permanently moved to the target URL. Browsers typically cache this response, meaning subsequent requests for the same short URL might go directly to the long URL, bypassing our server.

The response back to the client looks like this:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently Location: https://www.original-long-url.com

- 302 (Temporary Redirect): This suggests that the resource is temporarily located at a different URL. Browsers do not cache this response, ensuring that future requests for the short URL will always go through our server first.

The response back to the client looks like this:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found Location: https://www.original-long-url.com

How can we ensure short urls are unique?

Random number generator

This random number serves as the unique identifier for the URL. We can use common random number generation functions like Math.random() or more robust cryptographic random number generators for increased unpredictability. The generated random number would then be used as the short code for the URL.

Hash Function we could use a hash function to generate a fixed-size hash code. Hash functions take an input and return a deterministic, fixed-size string of characters. This is great because if two people try to generate a short code for the same long URL, they will get the same short code without needing to query the database. Hash functions also provide a high degree of entropy, meaning that the output is random and unique for each input and unlikely to collide.

With either the random number generator or the hash function, we can then take the output and encode it using a base62 encoding scheme and then take just the first N characters as our short code. N is determined based on the number of characters needed to minimize collisions.

Why base62? It’s a compact representation of numbers that uses 62 characters (a-z, A-Z, 0-9). The reason it’s 62 and not the more common base64 is because `we exclude the characters + and / single those are reserved for url encoding.

input_url = "https://www.example.com/some/very/long/url"

random_number = Math.random()

short_code_encoded = base62_encode(random_number)

short_code = short_code_encoded[:8] # 8 characters

Challanges

Despite the randomness, there’s a non-negligible chance of generating duplicate short codes, especially as the number of stored URLs increases.

To reduce collision probability, we need high entropy, which means generating longer short codes. However, longer codes negate the benefit of having a short URL. Detecting and resolving collisions requires additional database checks for each new code, adding latency and complexity to the system. The necessity to check for existing codes on each insertion can become a bottleneck as the system scales. Thus, introducing a tradeoff between uniqueness, length, and efficiency — making it difficult for us to achieve all three.

**Counter Based **

One way to guarantee we don’t have collisions is to simply increment a counter for each new url. We can then take the output of the counter and encode it using base62 encoding to ensure it’s a compacted representation.

Redis is particularly well-suited for managing this counter because it’s single-threaded and supports atomic operations. Being single-threaded means Redis processes one command at a time, eliminating race conditions. Its INCR command is atomic, meaning the increment operation is guaranteed to execute completely without interference from other operations. This is crucial for our counter - we need absolute certainty that each URL gets a unique number, with no duplicates or gaps.

Challenges

In a distributed environment, maintaining a single global counter can be challenging due to synchronization issues. All instances of our Primary Server would need to agree on the counter value. We’ll talk more about this when we get into scaling. We also have to consider that the size of the short code continues to increase over time with this method.

To determine whether we should be concerned about length, we can do a little math. If we have 1B urls, when base62 encoded, this would result in a 6-character string. Here’s why:

1,000,000,000 in base62 is ‘15ftgG’

This means that even with a billion URLs, our short codes would still be quite compact. As we approach 62^7 (over 3.5 trillion) URLs, we’d need to move to 7-character codes. This scalability allows us to handle a massive number of URLs while keeping the codes short and effectively neutralizing that concern.

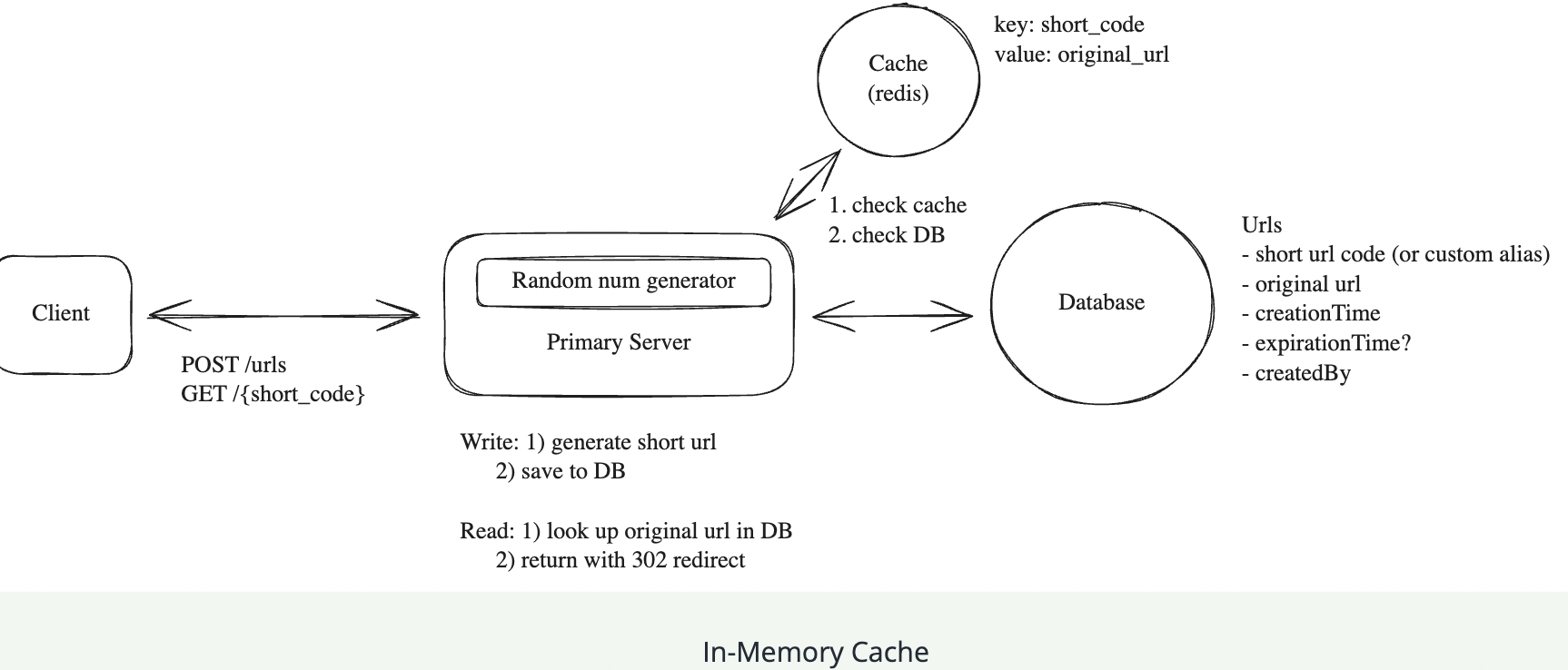

How can we ensure that redirects are fast?

_**indexing

To avoid a full table scan, we can use a technique called indexing.

Challenges

Relying solely on a disk-based database for redirects presents some challenges, although modern SSDs have significantly reduced the performance gap. While disk I/O is slower than memory access, it’s not prohibitively slow.

the main challenge lies in the sheer volume of read operations required. With 100M DAU (Daily Active Users), assuming each user performs an average of 5 redirects per day, we’re looking at:

`100,000,000 users * 5 redirects = 500,000,000 redirects per day 500,000,000 / 86,400 seconds ≈ 5,787 redirects per second

Multiplying by 100x to handle the spikes means we need to handle ~600k read operations per second.

Even with optimized queries and indexing, a single database instance may struggle to keep up with this volume of traffic. This high read load could lead to increased response times, potential timeouts, and might affect other database operations like URL shortening.

**InMemory cache for frequently accessed urls The key here is that instead of going to disk we access the mapping directly from memory. This difference in access speed is significant:

- Memory access time: ~100 nanoseconds (0.0001 ms)

- SSD access time: ~0.1 milliseconds

- HDD access time: ~10 milliseconds This means memory access is about 1,000 times faster than SSD and 100,000 times faster than HDD. In terms of operations per second:

- Memory: Can support millions of reads per second

- SSD: ~100,000 IOPS (Input/Output Operations Per Second)

- HDD: ~100-200 IOPS

Challenges

While implementing an in-memory cache offers significant performance improvements, it does come with its own set of challenges. Cache invalidation can be complex, especially when updates or deletions occur, though this issue is minimized since URLs are mostly read-heavy and rarely change. The cache needs time to “warm up,” meaning initial requests may still hit the database until the cache is populated. Memory limitations require careful decisions about cache size, eviction policies (e.g., LRU - Least Recently Used), and which entries to store. Introducing a cache adds complexity to the system architecture, and you’ll want to be sure you discuss the tradeoffs and invalidation strategies with your interviewer.

**CDN

the short URL domain is served through a CDN with Points of Presence (PoPs) geographically distributed around the world. The CDN nodes cache the mappings of short codes to long URLs, allowing redirect requests to be handled close to the user’s location

by deploying the redirect logic to the edge using platforms like Cloudflare Workers or AWS Lambda@Edge, the redirection can happen directly at the CDN level without reaching the origin server

Challenges

Ensuring cache invalidation and consistency across all CDN nodes can be complex. Setting up edge computing requires additional configuration and understanding of serverless functions at the edge. Cost considerations come into play, as CDNs and edge computing services may incur higher costs, especially with high traffic volumes. Debugging and monitoring in a distributed edge environment can be more challenging compared to centralized servers

How can we scale to support 1B shortened urls and 100M DAU?

Calculate Size of data

Each row contains: 200 bytes short code (~8 bytes) long URL (~100 bytes), creationTime (~8 bytes), optional custom alias (~100 bytes) expiration date (~8 bytes).

_We can round up to 500 bytes to account for any additional metadata like the creator id, analytics id, etc.

1B mappings, we’re looking at 500 bytes * 1B rows = 500GB of data. The reality is, this is well within the capabilities of modern SSDs.we can expect it to grow but only modestly. If we were to hit a hardware limit, we could always shard our data across multiple servers but a single Postgres instance, for example, should do for now.

`what database technology should we use? Most of the DBs will work here.

We could estimate that maybe 100k new urls are created per day. 100k new rows per day is ~1 row per second. So any reasonable database technology should do (ie. Postgres, MySQL, DynamoDB, etc).

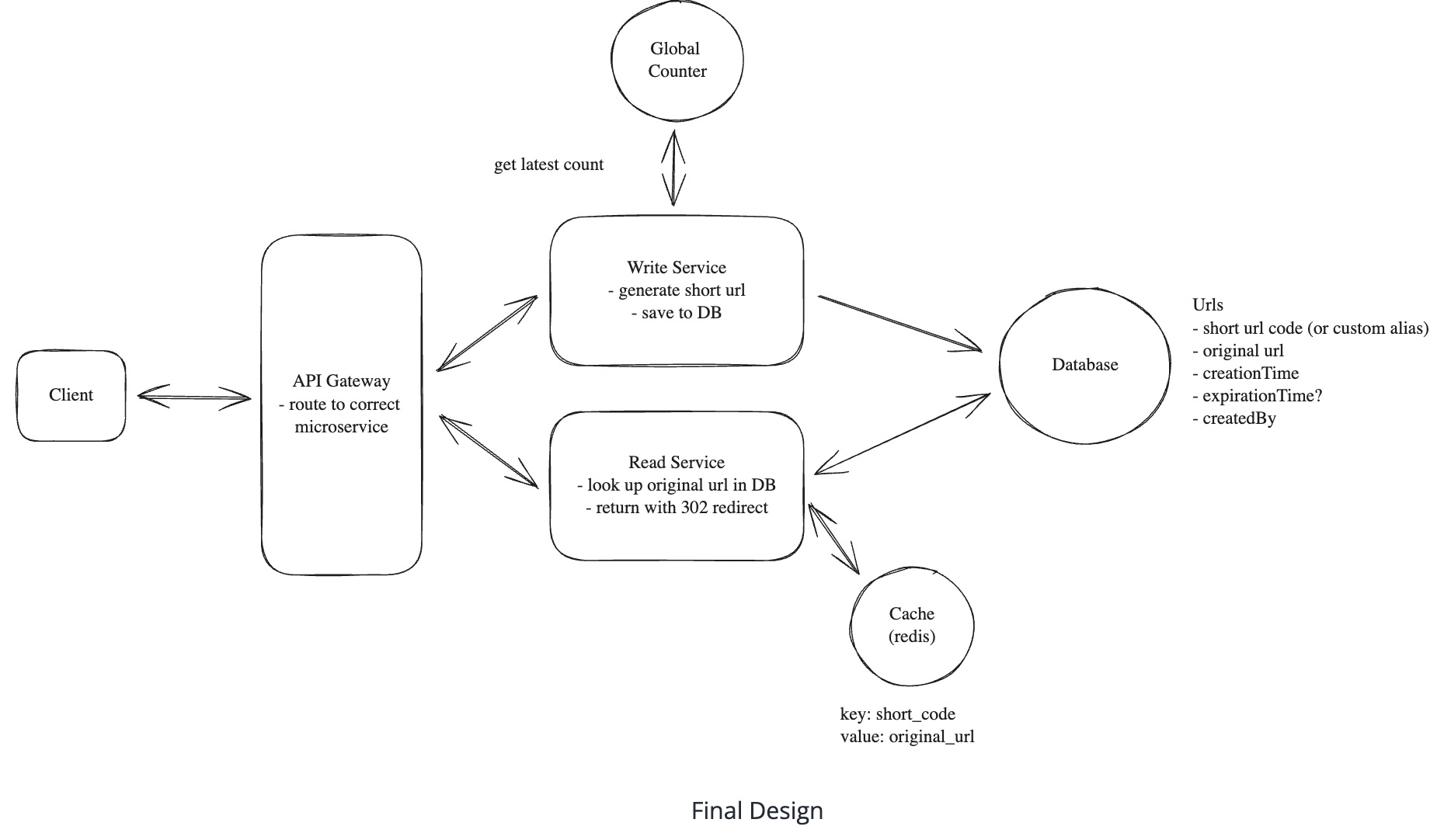

what if the DB goes down?

Database Replication

Database Backup

Reads are much more frequent than writes

We can scale our primary server by dividing read/write responsibility

Read Service handles redirects Write service handles the creation of new short urls

we can horizontally scale both the Read Service and the Write Service to handle increased load. Horizontal scaling is the process of adding more instances of a service to distribute the load across multiple servers

How to maintain unique counter in horizontally write scaled DB?

Horizontally scaling our write service introduces a significant issue! For our short code generation to remain globally unique, we need a single source of truth for the counter. This counter needs to be accessible to all instances of the Write Service so that they can all agree on the next value.

We could use centralized Redis instance to store the counterThis Redis instance can be used to store the counter and any other metadata that needs to be shared across all instances of the Write Service. Redis is single-threaded and is very fast for this use case. It also supports atomic increment operations which allows us to increment the counter without any issues. Now, when a user requests to shorten a url, the Write Service will get the next counter value from the Redis instance, compute the short code, and store the mapping in the database.

How can we avoid overhead of an additional network request to redis for each new write request?

“counter batching” to reduce the number of network requests

How it works

- Each Write Service instance requests a batch of counter values from the Redis instance (e.g., 1000 values at a time).

- The Redis instance atomically increments the counter by 1000 and returns the start of the batch.

- The Write Service instance can then use these 1000 values locally without needing to contact Redis for each new URL.

- When the batch is exhausted, the Write Service requests a new batch.

What if redis node goes down?

To ensure high availability of our counter service, we can use Redis's built-in replication features. Redis Enterprise, for example, provides automatic failover and cross-region replication. For additional durability, we can periodically persist the counter value to a more durable storage system.

Why is producing unpredictable short URLs mandatory for our system?

Attackers can have access to the system-level information of the short URLs’ total count, giving them a defined range to plan out their attacks. This type of internal information shouldn’t be available outside the system.

Our users might have used our service for generating short URLs for secret URLs. With the information above, the attackers can try to list all the short URLs, access them and gain insights about the associated long URLs, risking the secrecy of the private URLs. It will compromise the privacy of a user’s data, making our system less secure.

_Solution

If it became a requirement that we needed to support private urls, we’d:

- Add a layer of indirection (e.g., hash the sequential ID)

- Use a larger ID space to make enumeration impractical

- Implement rate limiting and monitoring for suspicious access patterns (we’d do this anyway).

Other problems:

`Lets say we have multiple instances of write service and 2 instances get same request i.e. same long url to convert to short one. How do we ensure idempotency here especially when we adopt a counter based approach ?

_We don’t need to ensure idempotency here. Having multiple short URLs for the same long URL is fine and even expected. It’s common for different users or instances to create separate short links for the same destination.

To support the custom alias feature, does it mean that a database check for an alias collision must always be run? A straight forward solution would be to continue generating and testing additional candidate short URLs until a collision is avoided? This seems non-optimal... What else can be done to help with avoid alias collision?

_The simplest solution is to use separate namespaces - auto-generated codes go under /a/ (like short.ly/a/abc123) and custom aliases under /c/ (like short.ly/c/my-brand). This way the counter-based generation never needs to check for custom alias collisions since they’re in completely different namespaces

The custom alias and counter systems are completely separate paths - they don’t interfere with each other at all. When a user requests a custom alias, we first check if it exists in the DB. If it does, reject it. If it doesn’t, use it. Only when users don’t specify a custom alias do we use the counter system. Custom aliases can even have a path prefix like /c/{alias}. Then even if the alias is a number, it can’t collide.