Functional requirement:

1. Upload a file/object in S3

2. Download a file object from S3 .

3. Versioning of objects

Non functional requirements :

1. Should be durable 6 nines (never loose a file)

2. Should be highly available 4 nines

3. Multitenency- same system available for multiple account

4. Scalable

5. Fault tolerant

Capacity estimation :

Assuming S3 has 100 PB of storage per year .

Average file size : 1mb

Total objects per year = 100*10^9/1 = 100 billion objects

Bucket - Container at which multiple objects or files are stored

Object : Payload which stores inside the bucket . Every object contains its metadata ,uuid and payload

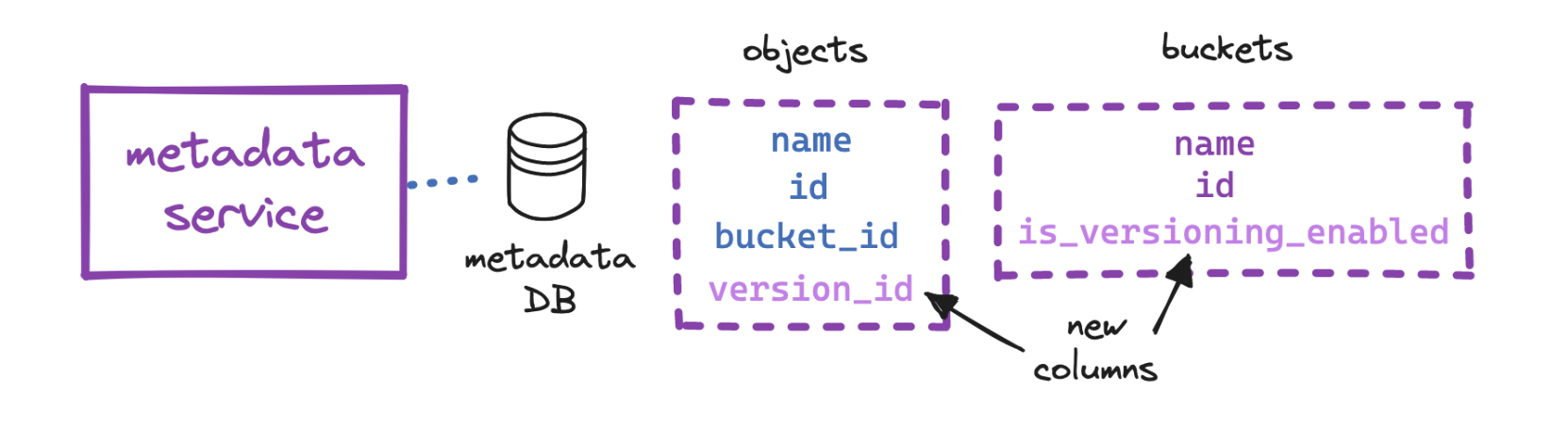

RDBMS for metadata:

Bucket

| bucket_id | bucket_name | time_created |

|---|---|---|

| Object |

| uuid | object_name | bucket_id | version | object_mapping | objectId | offset | filename | size |

|---|

Object mapping [This is used when we keep multiple objects under same file so to identify the object we use offset that where the object is being stored in file ]

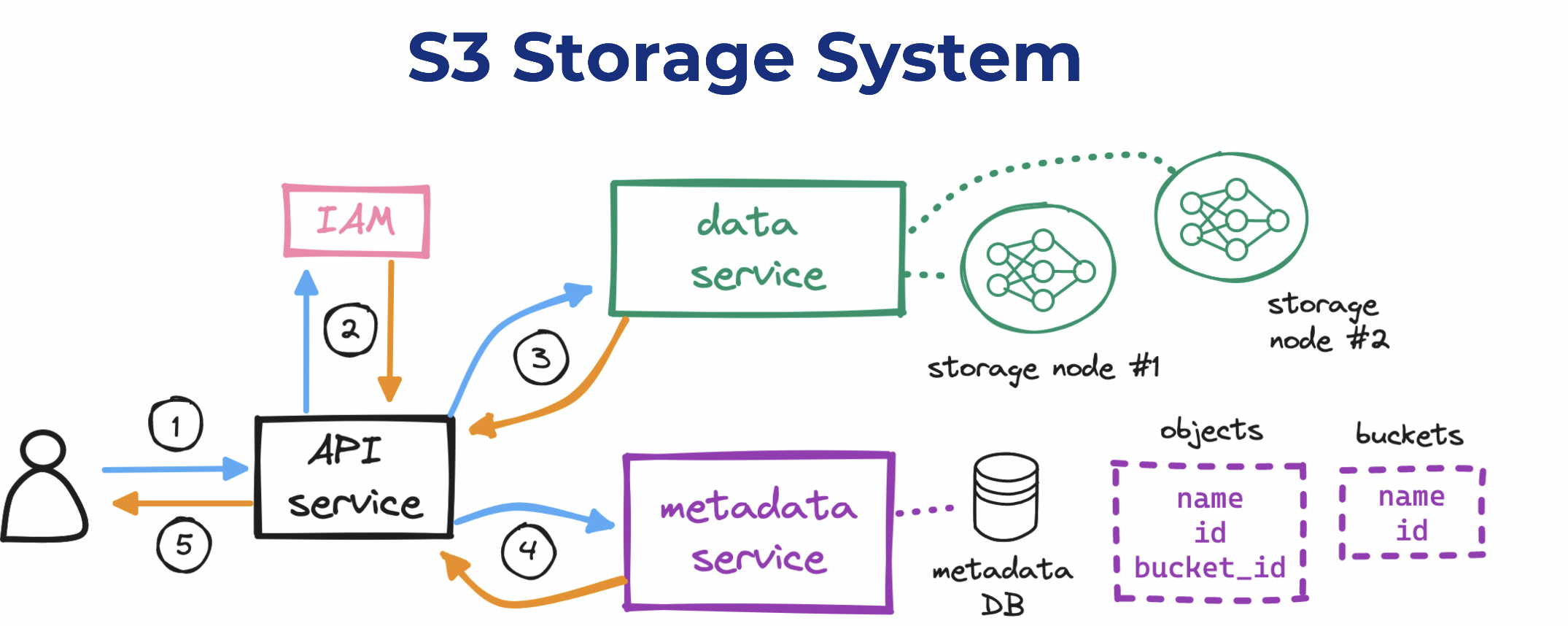

we can start to draft a high-level design for our S3 system:

- For reading and writing objects to disk, we need to set up a data service/Placement service.

- For reading and writing metadata for those objects, a metadata service.

- For enabling users to interact with our system, an API service.

- For handling user auth, identity and access management (IAM).

verify who the requesting user is (“authentication”),

- validate that their permissions allow the request (“authorization”),

- create a container (“bucket”) to place content into,

- persist (“upload”) a sequence of bytes and its metadata (“object”),

- retrieve (“download”) an object given a unique identifier,

- return a response with the result to the requesting user.

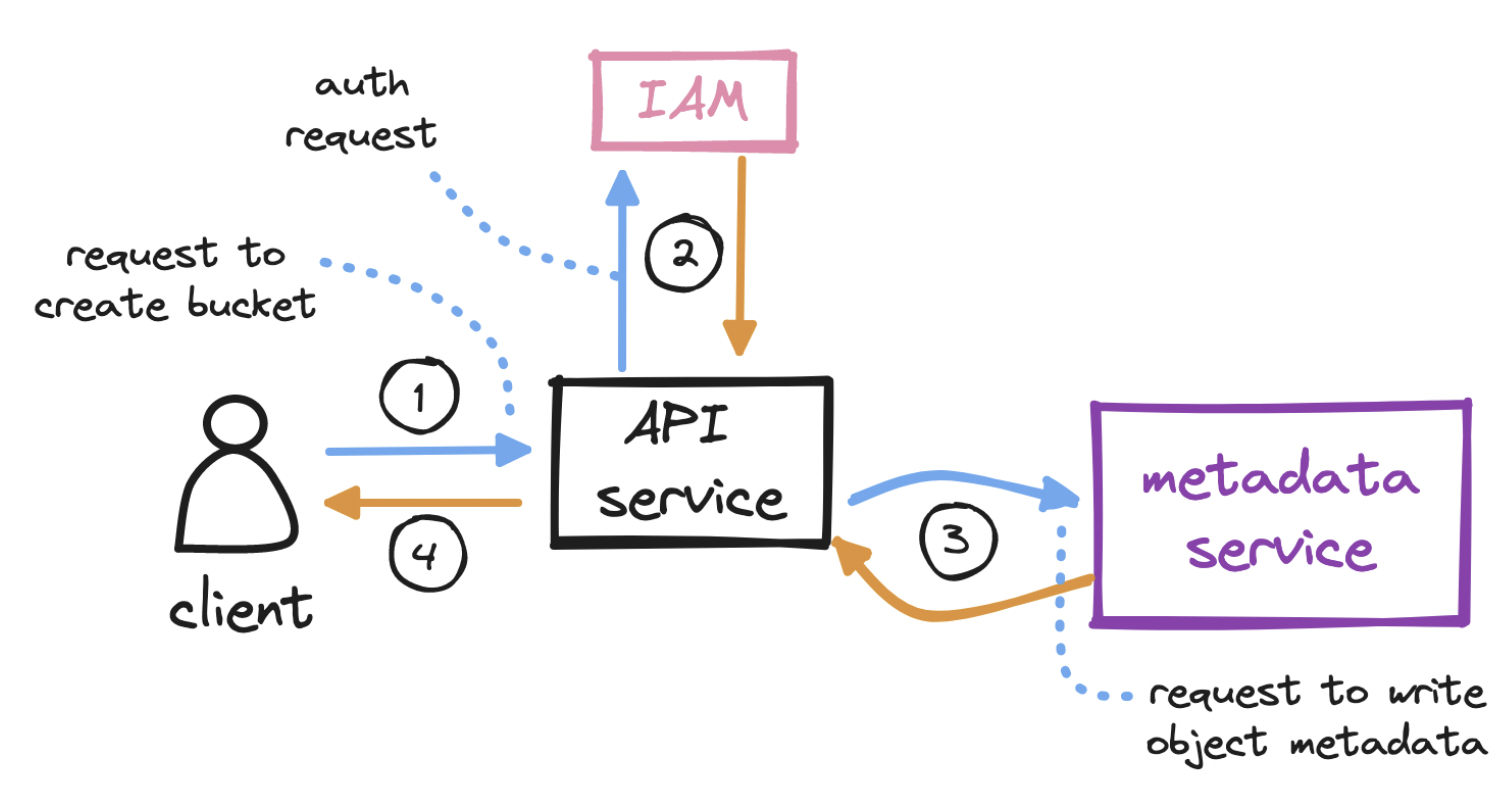

To create a bucket…

- The client sends an HTTP PUT request to create a bucket.

- The client’s request reaches the API service, which calls identity and access management (IAM) for authentication and authorization.

- A bucket, as we mentioned, is merely metadata. On successful auth, the API service calls the metadata service to insert a row in a dedicated buckets table in the metadata database.

- The API service returns a success message to the client.

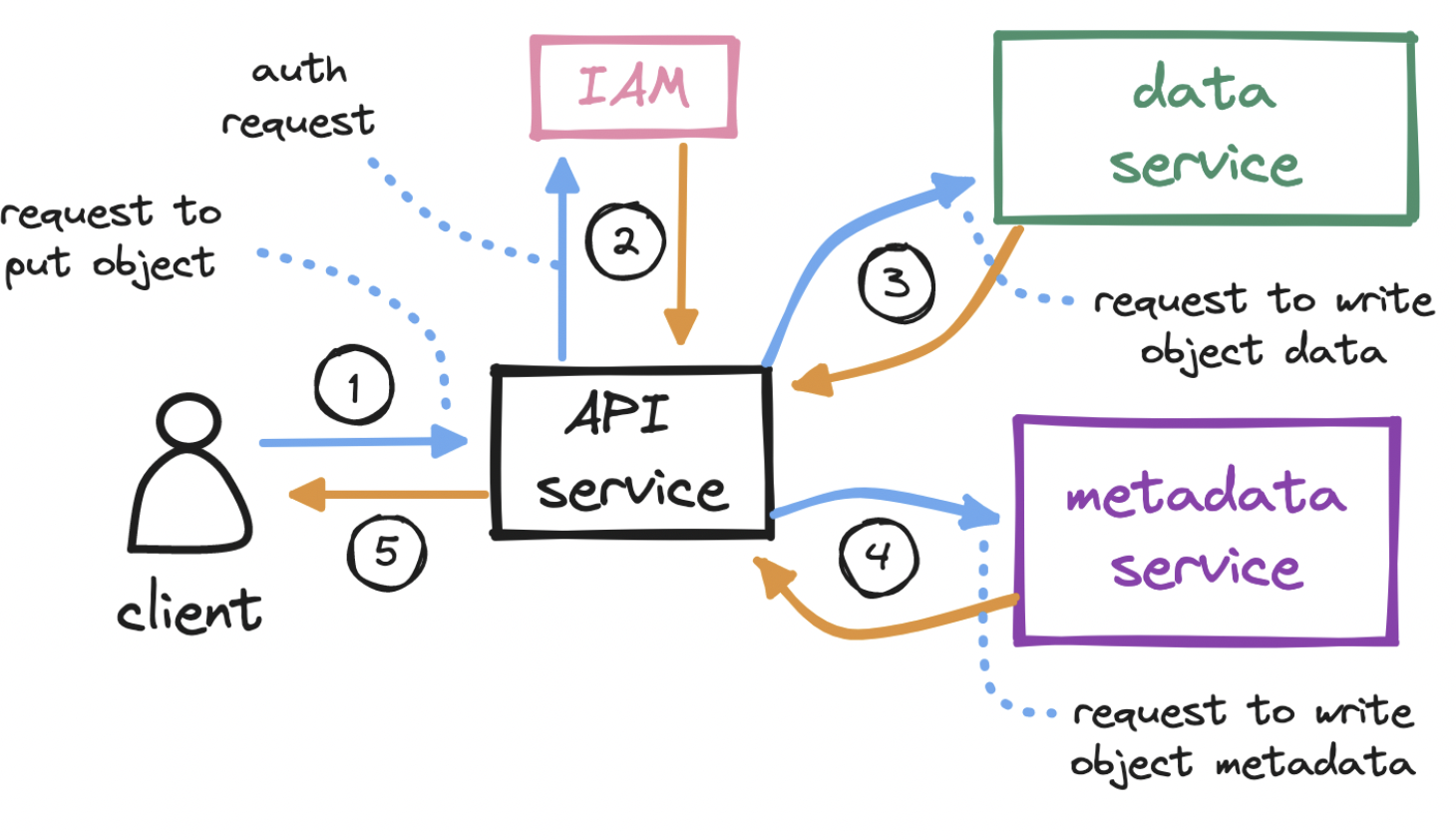

To upload an object…

- With the bucket created, the client sends an HTTP PUT request to store an object in the bucket.

- Again, the API service calls IAM to perform authentication and authorization. We must check if the user has write permission on the bucket.

- After auth, the API service forwards the client’s payload to the data service, which persists the payload as an object and returns its id to the API service. It generates the uuid of the object and figure out which data node need to store the object . Data service keeps the mapping of data node and its health and its keep virtual cluster map .Virtual cluster map keeps info of each data node and its replicas . Data service uses consistent hashing for storing and retrieving the data node .

- The API service next calls the metadata service to insert a new row in a dedicated objects table in the metadata database. This row holds the object id, its name, and its bucket_id, among other details.

- The API service returns a success message to the client.

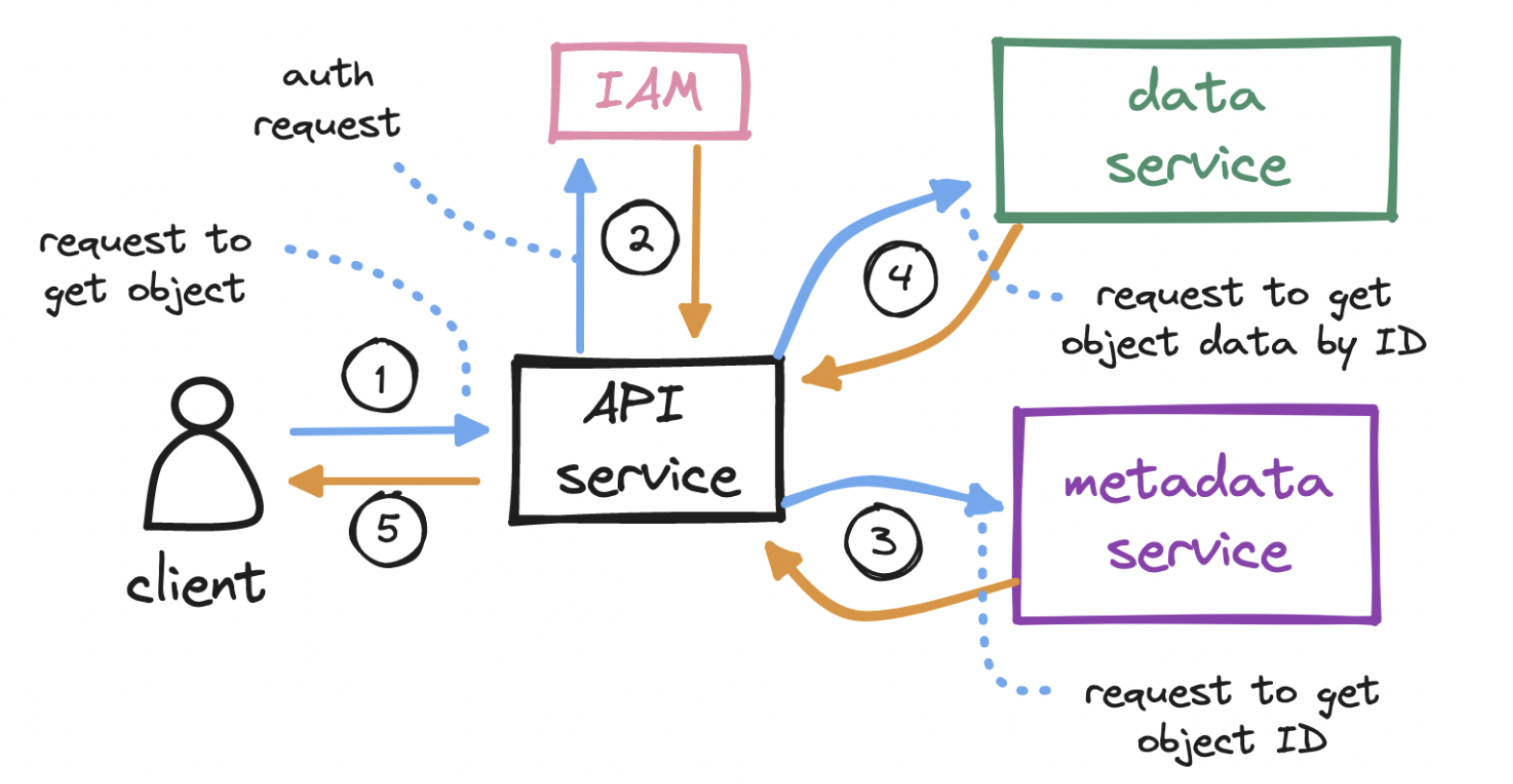

To download an object…

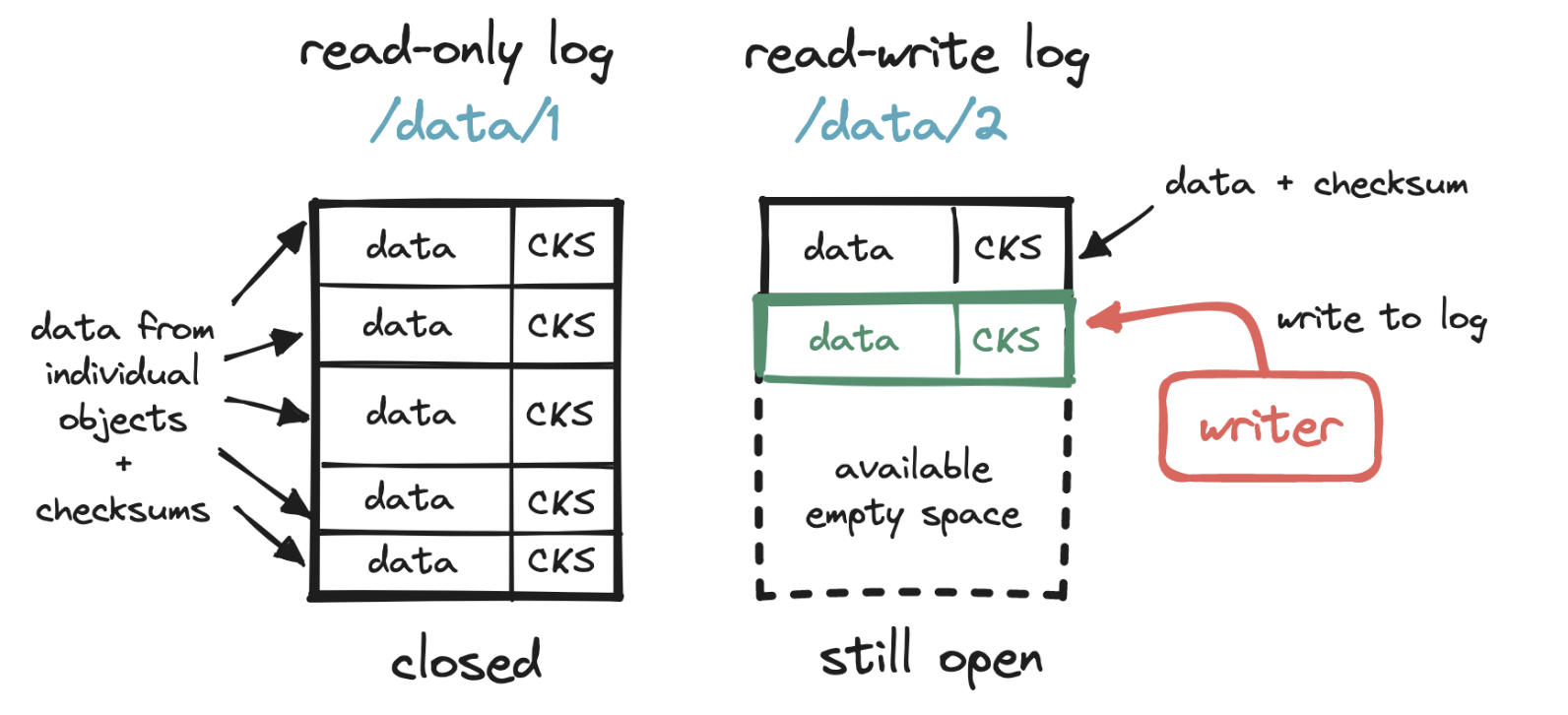

Let’s keep drilling down. How exactly do we write to a storage node? To make the most out of our disk, we can write multiple small objects into a larger file, commonly known as a write-ahead log (WAL). That is, we append each object to a running read-write log. When this log reaches a threshold (e.g. 2 GiB), the file is marked as read-only (“closed”), and a new read-write log is created to receive subsequent writes. This compact storage process is what accounts for S3 objects being immutable.

Typically, S3 systems cap the number of buckets allowed per user, so the size of our buckets table will remain bounded. If each user has set up 20 buckets and each row takes up 1 KiB, then one million users will require ~20 GiB. This can easily fit in a single database instance, but we may still want to consider provisioning read replicas, for redundancy and to prevent a bandwidth bottleneck.

The objects table, on the other hand, will grow unbounded. The number of rows, conceivably in the order of billions, will exceed the capacity of any single database instance. How can we partition (“shard”) this vast number of rows across multiple database instances?

- If we shard by object.bucket_id, causing objects in the same bucket to end up in the same partition, we risk creating some partitions that will handle much more load than others.

- If we shard by object.id, we can more evenly distribute the load. But remember: when we download an object, we call the metadata service and pass in both object.name and object.bucket_name in order to find object.id, which we then use to locate the actual data. As a result, this sharding choice would make a major query in the object download flow less efficient.

Other features S3 like applications supports:

Data integrity: We need a guarantee that the data we read is the same as the data we wrote. One solution is to generate a fixed-length fingerprint (“checksum”) from each sequence of bytes we write, and to store that fingerprint alongside the sequence. Consider a fast hash function like MD5. Later, at the time of retrieval, immediately after receiving data, we generate a new checksum from the data we received, and compare the new checksum to the stored one. A mismatch here will indicate data corruption.

Vast storage space: we rely on a write-ahead log to store objects and a small embedded DB to locate them.

Garbage collection: deletion and data corruption will produce unused storage space, so we need a way to reclaim space that is no longer used. solution is to periodically run a compaction process

- find the valuable sections of a set of read-only log files,

- write those valuable sections into a new log file,

- update object location details in the embedded DB, and

- delete the old log files.

Versioning: we can store multiple versions of the same object in a bucket, and restore them - this prevents accidental deletes or overwrites

Multipart uploads: With multipart uploads, we can upload objects in smaller parts, either sequentially or in parallel, and after all parts are uploaded, we reassemble the object from its parts. This is useful for large uploads (e.g. videos) that may take long and so are at risk of failing mid-upload. On upload failure, the client resumes from the last successfully uploaded part, instead of having to start over from the beginning

- The client requests S3 to initiate a multipart upload for a large object and receives an upload_id, a reference to the current upload session.

- The client splits up the object into parts (in this example only two, often more) and uploads the first part labeled as part_1, including the upload_id. On success, S3 returns an identifier (ETag, or entity tag) for that successfully uploaded part of the object.

- The client repeats the previous step for the second part, labeled as part_2, and receives a second ETag.

- The client requests S3 to complete the multipart upload, including the upload_id and the mapping of part numbers to ETags.

- S3 reassembles the large object from its parts and returns a success message to the client. The garbage collector reclaims space from the now unused parts.

Think41

41:

30-35: